Airborne microplastics: Where do they come from, where do they go?

Plastic dust is polluting the global environment: Microplastics – particles less than 5 mm in diameter – have been detected not only in in soils, freshwaters, and the ocean, but also in the air that we breathe. This could pose a threat to human health, as the smallest particles in particular can enter the respiratory system and the bloodstream. In addition, atmospheric microplastics are transported to and deposited in the most remote corners of the planet. But how do they enter the atmosphere in the first place?

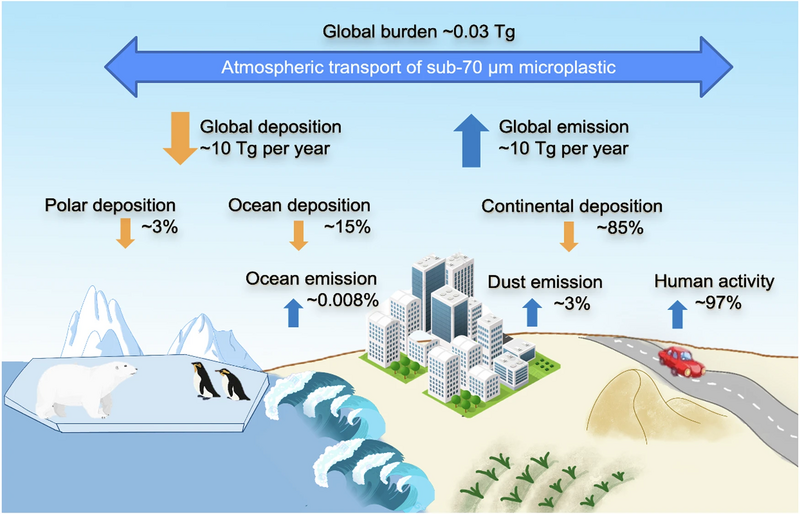

In general, the sources of microplastics are found on land – for example, fibers from synthetic clothing in domestic sewage, or car tire dust on the streets. Previous studies have suggested that a major pathway for them to enter the atmosphere is through the ocean: Microplastics are washed into rivers and carried out to the sea, where they accumulate. Air bubbles created by sea spray, wind, and waves can lift them out of the water and into the atmosphere. However, a new study led by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology (MPI-M) shows that the ocean’s role is mainly that of a sink – not a source, as previously thought.

The ocean: a massive or a negligible source of microplastics?

The assumption that the ocean acts as a source of microplastics to the atmosphere was based on inverse modeling. In this method, the sources of a substance are inferred from measurements of its atmospheric concentration distribution. Applied to microplastics, it led scientists to believe that there was an oceanic source of microplastics to the atmosphere of several hundred million or even several billion kilograms per year. The exact mechanism of how this transfer works was then investigated in laboratory experiments which led to a very different conclusion: Only a few thousand or hundred thousand kilograms per year seemed plausible.

Using a global atmospheric chemical transport model, an international team of researchers including former visiting researcher at MPI-M Shanye Yang and MPI-M group leader Guy Brasseur investigated whether the assumption of a small oceanic source leads to an atmospheric distribution of microplastics that is consistent with observations. The result was positive. Rather than being a source, the ocean appeared to be a sink, where 15% of all airborne microplastics are deposited.

Informing pollution reduction strategies

The study also shows how size determines the transport of microplastics in the atmosphere: Larger particles settle relatively quickly, either still on land or near the coastlines. Small microplastic particles can remain in the atmosphere for up to one year, facilitating their transport around the globe. For example, the model shows that the small particles, although emitted on the continent, travel as far as the Arctic region and are deposited on snow and ice. This shows the global impact of microplastic pollution. These insights can inform pollution reduction strategies, which should focus on the continental sources rather than the role of the ocean as a source of microplastics.

Original publication

Yang, S., Brasseur, G., Walters, S. et al. Global atmospheric distribution of microplastics with evidence of low oceanic emissions. npj Climate and Atmospheric Sciences 8, 81 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41612-025-00914-3

Contact

Dr. Shanye Yang

shanye.yang@mpimet.mpg.de

Prof. Guy Brasseur

Max Planck Institute for Meteorology

guy.brasseur@mpimet.mpg.de