50 Years of Climate Research at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology

In the depths of space, completely illuminated by the Sun, the Earth showed itself in all its beauty to the astronauts of the Apollo 17 mission on 7 December 1972: the intense blue of the ocean, the earthy brown tones of the land masses, the brilliant white of the Antarctic ice sheet and the dynamic structure of spiral and feathery cloud formations characterize the image of the blue planet. The “Blue Marble” photo captured the spirit of the early 1970s. It became one of the most widely used images in human history, and, in the early days of the environmental movement, it came to symbolize both the uniqueness and the vulnerability of the Earth.

It was no coincidence that the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology (MPI-M) was founded during this time. Concerns about the carrying capacity of the Earth and the suspicion that humans might be influencing the climate by emitting carbon dioxide were the subject of public debate. Research in Germany was under pressure to make progress, because it was lagging behind the rest of the world by about a decade.

Beginning with Atmosphere and Ocean

Against this backdrop, the Max Planck Society decided to establish a climate research institute. Hamburg was chosen because of the opportunity to incorporate parts of the renowned Fraunhofer Institute for Radiometeorology and Maritime Meteorology into the MPI-M. The physicist and mathematician Klaus Hasselmann was appointed as the founding director. At the opening of the MPI-M on December 5, 1975, he said that the name of the institute was due to the fact that there was no well-sounding German translation for the English term “atmosphere-ocean physics”. The plan for the MPI-M was not to conduct classical meteorology, but to understand the Earth's climate. Sooner or later, however, this endeavor had to go beyond the consideration of the atmosphere and the ocean, as Hasselmann explained: “(...) one must include other important components in a complete climatic system, such as the biosphere, (...) or the various chemical interactions in the cycle of trace substances and aerosols, which also determine the radiation budget of the atmosphere, and many other processes.”

But first, the institute devoted itself to the two main components of the climate system, which also stand out prominently in the Blue Marble photo: The ocean and – represented by the clouds in the photo – the atmosphere. Hasselmann built a new department on “Physics of the Ocean and Climate Dynamics”, while the second department on “Physics of the Atmosphere”, headed by meteorologist Hans Hinzpeter, initially consisted of staff from the former Fraunhofer Institute. Hinzpeter investigated exchange processes between the atmosphere and the ocean as well as the interaction of clouds, aerosols, water vapor and radiation. He performed observations, analyzed measurement data, and developed devices that could remotely measure (or sense) the properties of the atmosphere.

The Possibility of Climate Modeling

Hasselmann initially tackled fundamental questions: Are the observed climate variations at all deterministic, that is, can they be calculated in principle, or are they random? And how is it possible to tell which climatic changes are of natural origin and which are human-induced? He treated the weather as a natural disturbance in the climate system and showed that this assumed random noise, due to the ocean’s slow response, produces long-term variability in the climate system.

An important result of these investigations was that it was possible to distinguish between natural variability and external influences. Hasselmann developed a concept for how exactly this could be achieved mathematically as early as 1979. However, due to the limited computing capacity, it was not until the 1990s that he was able to apply this method with the help of advanced climate models.

First Ocean Circulation Models

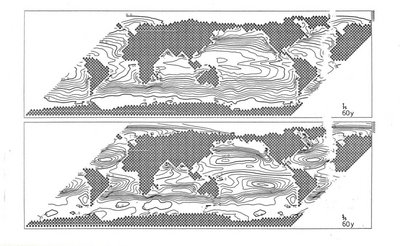

Parallel to Hinzpeter's observational research and Hasselmann's basic theoretical considerations, Hasselmann established modeling at the MPI-M, too. This scientific view of the blue planet requires the Earth’s atmosphere, ocean, and other components to be discretized. This can be accomplished by overlaying Earth's surface with a grid, which is extended likewise through the depth of the atmosphere, or the ocean, or into the land surface. Then values averaged over the resultant three-dimensional grid elements or grid boxes define the state of the system, which is evolved forward in time using physical laws and auxiliary assumptions. At the MPI-M, such a three-dimensional model was developed for the ocean by the physicist Ernst Maier-Reimer. The result was outstanding: The Large-Scale Geostrophic (LSG) ocean general circulation model was considered to be the fastest dynamic global ocean model of all time. In view of the very limited computing capacity at the time, this was a big advantage, especially when investigating processes on long time scales. Maier-Reimer also incorporated carbon chemistry into the model at an early stage. By integrating nutrients, biogeochemical processes were represented for the first time as well, resulting in the “Hamburg Ocean Carbon Cycle” model (HAMOCC). This pioneering effort was many years ahead of its time and has provided the basis for many studies of the carbon cycle in the ocean, helping to answer the question of how much carbon dioxide set free through human activities is absorbed by the ocean and how much remains in the atmosphere, causing additional warming.

Coupled Models and Increasing Computing Capacities

In addition to the LSG model, there was an alternative ocean circulation model, the isopycnal ocean model OPYC, developed by Josef Oberhuber. Maier-Reimer also presented another model, the Hamburg Ocean Primitive Equation Model (HOPE), which was initially mainly applied to the tropical Pacific. The first attempts to link the MPI-M ocean models with the atmospheric model of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) were made in the late 1980s.

The advances in modeling were made possible and accelerated by the expansion of local computing capacities, for which Hasselmann repeatedly sought funding. These ambitions were boosted when the German government's climate research program was established in 1982. As a result, Hamburg received its first supercomputer in the mid-1980s. In 1987, the Max Planck Society, the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, and the GKSS Research Center in Geesthacht (now Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon) jointly founded the German Climate Computing Center (DKRZ) as a service facility for climate research in all of Germany. While the predecessor only allowed for climate simulations with coupled models to reach about two years into the future, the Cray-2S supercomputer acquired in 1988 enabled calculations 100 years into the future. This illustrates how the availability of increasingly powerful computers has enabled the MPI-M to play a pioneering role in climate modeling – and it continues to do so today.

New People, New Impulses

In addition to the expansion of computing capacities, leadership changes played a role in the development of climate research at the MPI-M. Hans Hinzpeter's successor, Hartmut Grassl, was an expert in ground-based and satellite-based remote sensing. Since the 1970s, satellites had made it possible to permanently observe the blue planet from a distance. Grassl thus continued Hinzpeter's observational research, which had been carried out in close cooperation with the University of Hamburg, in an equally successful collaboration.

In 1991, the MPI-M was able to recruit the former director of the ECMWF, Lennart Bengtsson, for a third department for “Theoretical Climate Modeling”. Bengtsson then recruited Erich Roeckner, previously a faculty member at the University of Hamburg and an expert in planetary atmospheres, who had already started to transform the ECMWF's numerical weather prediction model into a climate model. This meant that longer time periods had to be calculated, which, given unchanged computing capacities, was only possible by reducing the spatial resolution. The model was given the name ECHAM – with the first two letters standing for the origin of the model (ECMWF) and the last three for Hamburg.

Climate Studies and Climate Change Scenarios

ECHAM was successfully coupled with all three ocean models. In the early 1990s, a group led by Stephan Bakan used the ECHAM/LSG model to determine how the fires in oil fields in Kuwait would affect the climate after the end of the Gulf War. With ECHAM/HOPE, Mojib Latif and colleagues conducted studies on the El Niño weather phenomenon. And ECHAM/OPYC was used, among other things, to study the North Atlantic circulation. In the long term, the ECHAM/HOPE combination prevailed, and HOPE became the MPI Ocean Model (MPI-OM).

The coupled atmosphere-ocean models also enabled calculations of how the climate would develop under future greenhouse gas emissions, using the scenarios of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which had been founded in 1988. The calculations were included in the annex to the IPCC's First Assessment Report published in 1992 – and in all subsequent reports up to the Sixth Assessment Report in 2021, as part of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) since 1995. The models helped the MPI-M gain international recognition. In 1995, an internal paper from the US National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) stated that the number one in climate modeling was no longer the USA, but Germany.

This pioneering role was reinforced by the proof that human activities are changing the Blue Marble. A group led by Gabi Hegerl applied the method developed by Hasselmann in 1979 to the coupled models. The scientists compared climate simulations that accounted for the human influence with those that did not, and showed that the probability that the observed temperature rise was only due to natural factors was less than five percent. Today, the number is even lower. For this “fingerprint” method, Klaus Hasselmann was awarded half the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2021 together with Syukuro Manabe, the other half going to the Italian physicist Giorgio Parisi.

A New Way Forward

The fingerprint study came at a time when international climate politics was gaining momentum: In 1992, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was agreed in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and in 1995 the parties met for the first time at the UN Climate Change Conference, which has been held annually ever since. However, the MPI-M did not initially benefit from this momentum. On the contrary: With the upcoming retirement of Bengtsson and Hasselmann as well as the absence of Grassl, who was on leave to work as Director of the World Climate Research Programme in Geneva, the Institute’s future was called into doubt. The MPG was already in a difficult financial situation following German reunification. At times, despite all its successes and international reputation, shuttering the MPI-M became a distinct possibility. It was only when Grassl returned from Geneva early and Hasselmann's successor was appointed that the institute was able to overcome the crisis.

With the promise to further expand the computing capacities, it was possible to recruit the atmospheric chemist Guy Brasseur from NCAR as the new director of the MPI-M on October 1, 1999. As a result, biogeochemical processes and aerosols were increasingly incorporated into the models developed at the MPI-M. While Brasseur's focus was on the atmosphere, Bengtsson's successor, Jochem Marotzke from the Southampton Oceanography Centre in the United Kingdom, reinvigorated ocean research and investigated sources of predictability rooted in the slow evolution of the ocean. Marotzke initiated a project that led to a model for decadal predictions, which has been used by the German meteorological service (DWD) since 2020.

Atmosphere, Ocean, Land: the Triad of the Earth System

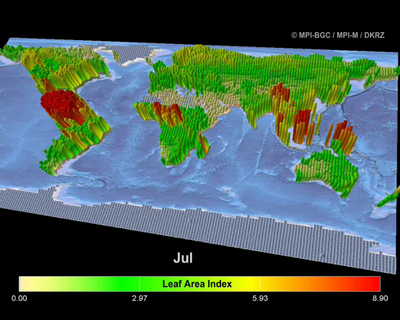

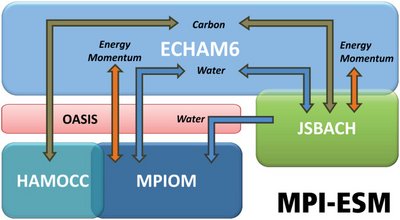

According on Hasselmann's statement at the opening of the MPI-M, a biologically active land surface was still missing for a complete view of the Earth system: the vegetation and soils, which influence the exchanges of energy and momentum through their structure and are essential for the carbon cycle. A group of scientists from the MPI for Biogeochemistry in Jena, which was founded in 1997, therefore came to Hamburg in 2001 to integrate the land biosphere into ECHAM. Initially referred to as “Green ECHAM”, the biosphere model was soon given the name JSBACH (Jena Scheme for Biosphere-Atmosphere Coupling in Hamburg), in reference to the MOZART atmospheric chemistry model that Brasseur had developed and brought with him to Hamburg.

Hartmut Grassl's successor, Martin Claussen – previously Deputy Director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research – took the Jena group into his department in 2005. He was interested in the interaction between the land surface, the vegetation, and the atmosphere, so his department at the MPI-M was called “The Land in the Earth System”. This marked the transition from the atmosphere-ocean modeling to a more comprehensive Earth system approach.

Bjorn Stevens succeeded Brasseur in 2008. Stevens, who had previously been Professor of Meteorology at the University of California in Los Angeles, researched the physics of the atmosphere – using both models and observations. These interests were well matched at the MPI-M, where he could build on the modelling legacy of Bengtsson and Roeckner, and observational advances from the research of Hinzpeter and Grassl. In 2010, together with partners from Barbados, he set up a cloud observatory on the Atlantic island and from 2013, in cooperation with the University of Hamburg, he made intensive use of the HALO research aircraft for observations of clouds and atmospheric circulation to test ideas emerging from the types of models the institute, and others worldwide, had been developing.

The numerous model developments for the various components of the Earth system – ECHAM, HOPE/MPI-OM, HAMOCC, JSBACH, MOZART – were interlinked and could be combined in a common, comprehensive model. With the coupled Earth system model MPI-ESM, the institute had developed a powerful tool. It, and the ideas that sprang from its use, not only influenced many climate assessments and public awareness of climate change, but were also used for studies on the planet's climate history. Under the leadership of Johann Jungclaus, the Institute investigated climatic changes over a period of 1200 years as part of the “Millennium Project”. It was the first demonstration of the capabilities of the MPI-ESM: The researchers specified external drivers – for example, solar activity, Earth's orbital parameters, greenhouse gas emissions, land use, and volcanic eruptions – and let the physics and biogeochemical processes encoded in the model do the rest. The MPI-M had thus secured itself a leading position in Earth system modeling.

A Radical Change in Modeling

At various points, however, the MPI's workhorse also reached its limits. The chemistry required a type of mathematical formulation that ECHAM was not designed for. Furthermore, it seemed that ECHAM could not efficiently utilize the parallel computing structure of modern supercomputers.

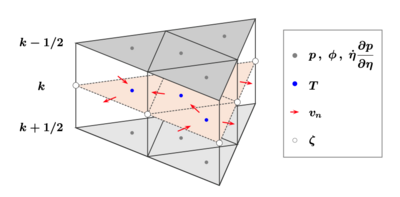

And then there was the shape of the grid. The longitude/latitude grid used until then had a disadvantage: Since the longitudes converge at the poles, the grid cells become smaller and smaller, causing mathematical problems and forcing the scientists to treat the North and South Poles as special cases. They were therefore looking for a grid whose cells were the same size everywhere on Earth – a body consisting of many similar surfaces with the greatest possible symmetry. This criterion is fulfilled by so-called Platonic solids, of which there are five types – including the icosahedron with 20 equilateral triangles.

Was it possible to use this Platonic solid as the basis for a new grid and thus for a new climate model? The mathematician Luca Bonaventura was recruited to investigate this question with a substantially simplified two-dimensional model with which he obtained encouraging results. However, designing a completely new and different climate model from scratch was a complex task that required innovative ideas and patience. The potential scientific gain was promising, however, and so the directors Stevens, Marotzke, and Claussen decided to go ahead with the development of the new model together with the DWD. It was not only the grid that was new but also the type of equations. The model was therefore given the name ICON (icosahedral non-hydrostatic).

A New Earth System Model

Initially, the scientific community was skeptical: The triangular grid had the peculiarity of favoring “wrong” solutions of the model equations in three-dimensional models. A group led by Peter Korn developed creative calculation methods to avoid this problem in the ocean component of ICON. Through a close collaboration with scientists at the DWD, a group led by Marco Giorgetta used other methods to help mitigate these problems in the atmosphere. They navigated the difficulties of translating the craftsmanship of Roeckner’s ECHAM to the new equations and grids adopted by ICON, thereby giving birth to ICON’s atmosphere component. Meanwhile Christian Reick and colleagues advanced developments to create new and more biologically active land models, and together with DKRZ new methods for coupling the varied components were created.

Despite the steady advances of ICON, through most of the past decade the MPI-ESM remained the workhorse of the Institute. Just recently, a group led by Uwe Mikolajewicz successfully incorporated an interactive ice-sheet model to simulate climate changes since the peak of the last ice age – the past 20,000 years – with the MPI-ESM.

Over time, the advantages of ICON began to impose themselves. Thanks to a national project led by the MPI-M, researchers across Germany cooperated to enable ICON to run at exceptionally high spatial resolution over large and eventually global spatial domains, on some of the largest computers in the world. This made it possible to represent climate processes more physically. The empirical handwork that had influenced model development for decades was avoided and the modeling activity was brought in harmony with the institute’s growing observational contributions.

Using the capability, almost to the day that the iconic “Blue Marble” photo turned 50 years old, a group led by Daniel Klocke demonstrated the ability of ICON to represent the fully coupled climate system on a scale of just one kilometer: Thanks to support from the computing company NVIDIA who helped with visualization, and the DKRZ for helping to navigate the challenges of next-generation computing, they simulated and visualized the state of the Earth at the time the photo was taken. This was basically a two-day prediction of the image that the astronauts must have seen during their mission. The similarity between the “real” Blue Marble and the simulation was striking. The scientists had tamed the complexity of the Earth system and mapped the blue planet in impressive detail.

Open Questions of Societal Relevance

In addition to the impressive demonstration of what is possible, the real relevance of the high-resolution simulations lies in their capacity to help scientists to create a more physical laboratory for testing their ideas and linking them to processes they can observe. Today, scientists at the MPI-M are investigating remaining puzzles in climate research, for example in the department of Sarah Kang, previously a professor at the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology in South Korea, who succeeded Martin Claussen as Director in 2023. These puzzles include the question of why a very large expanse of the eastern Pacific Ocean has cooled contrary to predictions and how this is linked to processes in distant regions of the Earth. Because small-scale processes often mediate between large-scale processes, high-resolution models hope to provide insights that have eluded the more statistical methods limiting earlier generations of models.

The question of how climate change will play out regionally, which is particularly relevant today in view of rising global temperatures, cannot be answered without a deep understanding of the physical processes at the kilometer scale. The fact that these can now be represented in Earth system models is not only due to the development of the model, but also once again to the greatly increased computing capacities – and the fact that the ICON code has been adapted in a forward-looking manner for the most modern high-performance computers. From May 2025, Europe's fastest supercomputer JUPITER will go into operation at Forschungszentrum Jülich, and in a project led by Cathy Hohenegger, MPI-M researchers and their partners are preparing simulations with the coupled Earth system model ICON with a resolution of just one kilometer for an entire year instead of just a few days.

The institute is also looking into the question of how information obtained in this way can be made available to broad user groups, for example in the “Destination Earth” project or as part of the global “Earth Virtualization Engines” (EVE) initiative. This much has become clear over the past few years: Climate change is already noticeable all over the world and requires carefully planned adaptation measures. The increasing number of climate-related extreme weather events and the crises they and more chronic changes cause make one thought resonate: Far greater than the vulnerability projected onto the iconic photograph of the blue planet is, in fact, the vulnerability of its inhabitants.

Further Information

History of the Institute

50 Years of Climate Research - Events 2025

Contact

Prof. Dr. Jochem Marotzke

Managing Director

Phone: +49 (0)40 41173-440

jochem.marotzke@mpimet.mpg.de

Dr. Denise Müller-Dum

PR and Communication Officer

Tel.: +49 (0)40 41173-387

denise.mueller-dum@mpimet.mpg.de