Southern Ocean warming leads to wetter Pacific coasts for centuries to come

People along the densely populated Pacific coasts are exposed to strongly fluctuating rainfall patterns: In East Asia, heavy rain falls in summer and flooding is already one of the climate risks in this region today. The western USA, on the other hand, is often hit by extreme drought in summer, and the question of how much precipitation the winter will bring is fundamental to appropriate preventive measures. Climate models predict that East Asia will experience even wetter summers and the western USA wetter winters in the future. However, there are considerable uncertainties in these two regions of all places.

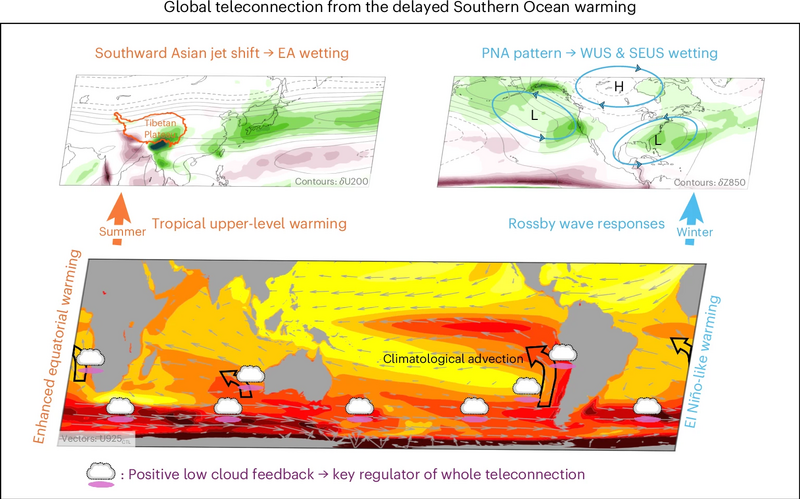

An international team of researchers has shown why this is the case and how the distant Southern Ocean determines precipitation on the Pacific coasts. The study was designed by Hanjun Kim from Cornell University (USA) and Sarah Kang from the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology (Germany) and carried out together with scientists from the US, the United Kingdom and South Korea. Using a climate model, they investigated the astonishing teleconnection that begins in the Southern Ocean, continues across the tropical Pacific and ultimately determines the weather patterns on the Pacific coasts. The analysis also entails an explanation as to why different climate models have so far delivered differing projections.

From the ocean via the atmosphere to the studied regions

The Southern Ocean has so far absorbed additional heat from the anthropogenic greenhouse effect and stored it away in the depths. But this storage capacity is declining – and gradually the Southern Ocean as a whole will warm up. This is where a chain reaction, known among experts as a teleconnection, begins: the warming over the Southern Ocean propagates toward the equator via the southeasterly winds and amplified by various interactions between the atmosphere and the ocean. Specifically, the warming from the Southern Ocean effectively evaporates the low cloud decks, which would otherwise reflect radiation, amplifying the warming toward the equator. Consequently, the equatorial ocean is warmed up with a pronounced warming over the eastern Pacific – similar to the "El Niño" weather phenomenon, which is characterized by a warm eastern Pacific and a comparatively cooler western Pacific.

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Kim et al. Nat. Geosci. (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-025-01669-5

Now the teleconnection continues in the atmosphere as in the "El Niño" situation: on the one hand, the equatorial ocean warming causes the Asian jet to shift southwards in summer. This increases its interaction with the Tibetan Mountains, which generates atmospheric flows that carry more moisture into the East Asian rain band. The monsoon rains in summer therefore intensify.

On the other hand, the tropical Pacific warming enhances precipitation in the western USA by altering the atmospheric circulation as in the El Niño situation. The stronger southwesterly winds enhance the moisture supplies and the eastward extension of the Pacific jet drives moisture-laden storms towards the American west coast, enhancing the precipitation in winter.

Clouds as mediators

The low-lying clouds over the subtropical Pacific play a decisive role in how the teleconnection from the Southern Ocean manifests itself quantitatively. The strength of the low cloud evaporation in response to the same amount of warming differs between the climate models, partially explaining why different models produce different results with regard to precipitation on the Pacific coasts. Corresponding improvements and dedicated measurement campaigns for the Southern Hemisphere low clouds could therefore reduce the uncertainty of the projections.

The researchers emphasize that the teleconnection becomes apparent on a time scale of centuries, as the Southern Ocean is warming very slowly. East Asia and the western USA will therefore have to deal with this consequence of global warming for a long time to come, even if climate protection efforts are successful, which must be taken into account in long-term adaptation strategies.

Further information

Article in the Cornell Chronicle

Original publication

Kim, H., Kang, S.M., Pendergrass, A.G. et al. Higher precipitation in East Asia and western United States expected with future Southern Ocean warming. Nature Geoscience (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-025-01669-5

Contact

Prof. Dr. Sarah Kang

Max Planck Institute for Meteorology

sarah.kang@mpimet.mpg.de